A growing number of automotive companies want to move their investments from Germany to other countries. In terms of investment attractiveness, Poland takes the lead.

The automotive industry in Germany is in decline and pulls the entire German economy down with it. Production levels of Germany’s largest vehicle manufacturers have fallen by more than 36% in ten years in Germany, while overseas production has risen from 8.6 million to more than 10 million, reports Handelsblatt, citing data from the Marklines news website. This crisis is particularly affecting the automotive industry.

The German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA) recently conducted a survey of automotive suppliers and medium-sized manufacturers of trailers, bodies and buses.

85% of the companies surveyed said that bureaucracy represents a heavy or even very heavy burden for them.

Electricity costs also remain one of the main challenges for automotive suppliers and medium-sized automotive companies in Germany. 71% of companies say that high electricity prices are a heavy or even very heavy burden for them.

Companies are also complaining about the situation regarding their orders. While as recently as May, 42% of companies said that a lack of orders was currently only a minor challenge or not a challenge at all, in the latest survey only 22% held this view. The survey also shows a growing trend for companies to relocate their investments. More than a third of businesses (35%) plan to move their investments abroad, up from 27% in May 2023. Only 1% of the companies surveyed intend to increase their investments in Germany in light of the current situation. According to the survey, the relocation destinations are other EU countries, Asia and North America (in that order).

Our survey clearly shows that medium-sized automotive companies in Germany suffer immensely from excessive bureaucracy and high energy costs. The fact that more and more companies are moving investments abroad is a wake-up call for Berlin! We need to take countermeasures and replace small regulatory steps with long-term strategies for greater competitiveness, says VDA president Hildegard Müller.

Production shifts to Eastern Europe In terms of investment attractiveness, Poland took the leading position as a relocation destination – ahead of the Czech Republic and Romania.

According to the Polish-German Chamber of Industry and Commerce, 6,000 German subsidiaries are currently based in Poland, employing a total of approximately 430,000 people. German companies have invested $40 billion to date.

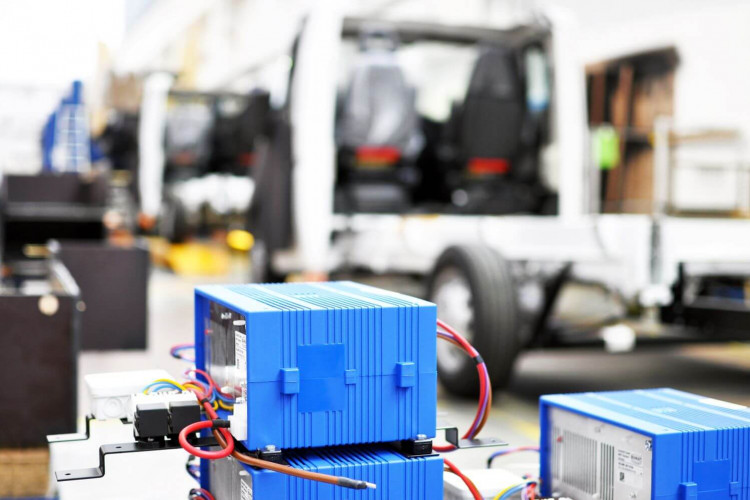

Many companies recognised Poland’s potential as an investment destination years ago. One example is vehicle manufacturer Mercedes-Benz, which is steadily expanding its production in the country. July saw the start of construction work on the manufacturer’s third factory in Poland, where electric vans will be built in the future. The location was chosen as part of a reorganisation of the company’s European production network, as it will enable the van division to optimise costs and the supply chain.

That said, an increasing number of foreign companies based in Germany are also moving to Eastern Europe.

In September, French automotive supplier Valeo announced that 300 jobs were being cut at its plant in Bad Neustadt in the Rhön-Grabfeld district. Going forward, electric motors will be produced at the Czechowice-Dziedzice plant.

Cooper Standard, a manufacturer of sealing systems for the automotive industry based in Novi, Michigan, also plans to relocate around 60 jobs from Lindau on Lake Constance to Poland.

A study by the German Economic Institute (IW) shows that companies withdrew more money from Germany in 2022 than ever before. In total, around $132 billion (€125 billion) more direct investment flowed out of Germany in the same period than was placed in the country. This trend is continuing.

Investment conditions in Germany have recently deteriorated again due to high energy prices and a growing shortage of skilled labour, says Christian Rusche, economist at IW.

The Institute warns that, in the worst case scenario, this could mean the beginning of deindustrialisation.